Your confusion is not evidence of inadequacy.

It's evidence of intelligence.

The more capable you are, the more options you see.

The more options you see, the more variables you track.

The more variables you track, the more paralysed you become.

When my business wound up, I sat in my room around 2 AM with 14 Google Drive folders open.

Each one representing a "serious path": Excel sheets for micro brewery costs, government pitch decks I'd travelled to present, 40,000 words of a novel manuscript, and content calendars for four platforms simultaneously.

I wasn't indecisive.

I was under-organised.

And here's the trap: I kept seeking more clarity through more research. More frameworks. More podcasts. More advice. But every new input added noise, until I couldn't see anything clearly.

The illusion: more information creates better decisions.

The reality: more information creates cognitive overload.

I Learned This the Hard Way

Six months of research had turned three clear options into 14 "serious possibilities." I'd genuinely invested in each one. Not dabbling - committed.

I built business models for microbreweries. Travelled to pitch a government-funded entrepreneurship platform. Wrote manuscript chapters at 3 AM. Learnt animation, scriptwriting, and communication skills. Generated content ideas for social media.

Each folder in my Google Drive represented hundreds of hours. Each future avatar of me needed a different “daily schedule” with each minute planned, yes, literally all 1440 minutes of the day.

I thought I was being strategic.

I was being scattered.

Here's what I didn't understand then: there's actual science behind why more research creates more confusion, not less.

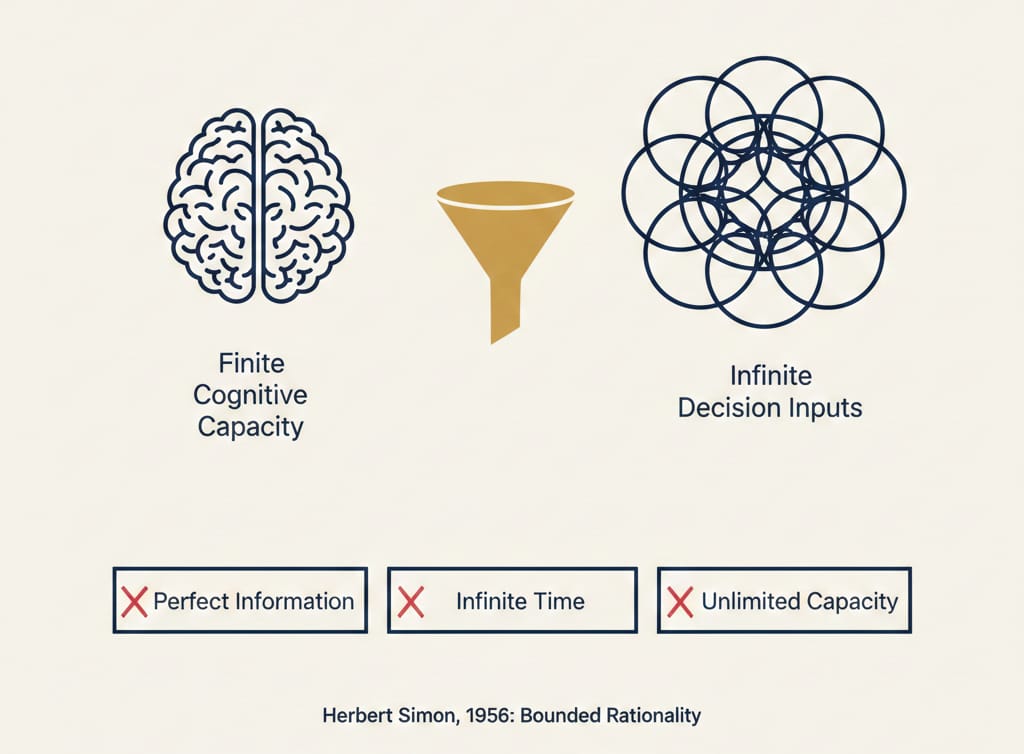

Herbert Simon, who won a Nobel Prize for this insight, wrote:

"The capacity of the human mind for formulating and solving complex problems is very small compared with the size of the problems whose solution is required for objectively rational behaviour in the real world."

Your brain isn't built to optimise for perfect decisions. It's built to make "good enough" decisions with limited information.

When you try to gather all the information, you're fighting your cognitive architecture, not using it.

So the question isn't "How do I get more clarity?" The question is: "How do I eliminate enough noise to see what's actually in front of me?"

The Elimination Advantage

Most people add information when confused. I did the same.

But high-performers eliminate options. That's the difference.

You can't organise chaos by adding more systems. You need to eliminate enough noise to see what's evaluable.

Because the question isn't "Which option is best?" The question is "Which options can I actually evaluate with resources I have?"

That shift changes everything.

Let me show you how this works.

1. Map the Noise

Your confusion isn't created by lack of clarity. It's created by unacknowledged volume.

Herbert Simon's bounded rationality teaches us this: human cognitive capacity is finite. When inputs exceed processing capacity, the system doesn't slow down, it freezes.

Your brain isn't broken. It's correctly signalling: "Too many inputs, insufficient architecture."

The act of inventory creates distance. When everything lives in your head, it's entangled. When it's externalised, written down, it becomes observable.

Observable = Organisable.

For me, this meant facing the truth: The brewery required Excel sheets I'd spent weeks building. The government platform meant travel, pitches, months of relationship-building. The novel meant 40,000 words already written. The content meant calendars for four platforms I was trying to maintain.

I thought I was keeping options open.

I was drowning in uncommitted possibilities.

The moment you write "I'm seriously considering 14 different paths," your brain can finally see why you're paralysed. That's not defeat. That's data.

You can't eliminate what you haven't named.

But seeing the noise is just the start.

2. Constraint Filter

Most options aren't actually available to you, they just haven't been eliminated yet.

This is where bounded rationality becomes practical. Herbert Simon showed that perfect decisions require perfect information, infinite time, and unlimited cognitive capacity.

You have imperfect information, finite time, and limited capacity.

Therefore: the goal isn't optimal choice. It's "good enough" choice from evaluable options.

Constraint isn't limitation. It's liberation.

This principle isn't new. Lao Tzu taught it 2,500 years ago, though we keep forgetting it:

"To attain knowledge, add things every day. To attain wisdom, remove things every day."

Knowledge is accumulation. Wisdom is elimination.

The courage to subtract what you can't evaluate so you can see what remains.

Here's how I applied this to my 14 folders:

Filter 1: Information Access "Can I gather necessary information within 7 days with zero budget?"

Government platform: Required 6-month approval timeline. Eliminated.

Microbrewery: Required £40,000 startup capital I didn't have. Eliminated.

Book: Required existing audience. I had under 300 friends on a dying social media platform. Eliminated.

Filter 2: Immediate Sustainability "Can this generate income within 60 days?"

Motion graphic novels: 6-month production minimum before revenue. Eliminated.

Fiction writing: 18-month manuscript-to-agent-to-publisher timeline. Eliminated.

Filter 3: Aligned Capacity "Can I execute this with skills I have today?"

Business consulting: Yes. Ten years' experience. Viable.

Content creation (focused): Yes. Been writing for years. This would be an extension. Viable.

14 folders became two viable options.

Not because 12 were inferior.

Because they were unevaluable or unsustainable with constraints I actually faced.

Here's the mistake people generally make: they treat constraint as failure. "I should be able to evaluate everything thoroughly."

That's fighting bounded rationality instead of working with it.

The eliminated paths aren't dead. They're deferred.

If circumstances change, they return to the field. But right now, they're consuming attention without possibility of resolution.

That's the definition of noise.

Now here's where courage enters.

3. Good-Enough Choice

After elimination, what remains isn't "the answer". It's "the field of possibility."

Clarity isn't certainty. It's organised uncertainty.

Information has diminishing returns.

The first 20% of research provides 80% of clarity.

The next 60% of research provides 15% more clarity.

The final 20% of research provides 5% more clarity, but consumes 80% of your time and attention.

If you've made it to Part 2 elimination, you've already done the 20% of research that matters.

What remains isn't insufficient information. It's the irreducible uncertainty of reality. No amount of research removes that.

I used to confuse "good enough" with "settling."

Wrong frame. "Good enough" doesn't mean giving up on excellence.

It means sufficient clarity given human cognitive limits.

Excellence comes from acting and iterating, not from perfect initial choice.

You'll never feel certain. Certainty is an illusion, not an emotion.

What you'll feel is organised uncertainty plus courage.

That's the signal.

"Courage isn't absence of fear. It's action despite fear (after you've organised what's knowable.)"

Viktor Frankl learned this in the most extreme circumstance imaginable - a concentration camp. If anyone understood acting with constraints, it was him:

"Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms - to choose one's attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one's own way."

Frankl had zero control over his circumstances. But he had complete sovereignty over his response.

You have far more freedom than Frankl did, but the principle is the same.

Constraints don't eliminate choice. They clarify it.

You're not choosing between perfect analysis OR blind action.

You're integrating both: systematic elimination plus courageous movement.

Now Here's How It All Connects

Part 1 makes the invisible visible.

Part 2 removes what you can't evaluate.

Part 3 moves you forward with what remains.

That's not a perfect system. It's a complete system.

You're not the person who can't decide.

You're the person learning to eliminate systematically and act courageously.

That's a completely different kind of person.

Carl Jung spent his life studying how we relate to circumstances without being defined by it. He wrote: "I am not what happened to me, I am what I choose to become."

But Jung wasn't talking about positive thinking or manifesting. He was talking about ontological freedom, the recognition that your essence exists independent of conditions.

You can use circumstances as constraints to clarify choice without being determined by those circumstances.

That's the difference between reaction and sovereignty.

Clarity isn't certainty. It's courage. The courage to act with organised uncertainty. Because you've eliminated what you can, and accepted what you can't.

The path forward isn't found. It's cleared.

The question isn't whether you'll face uncertainty.

You will.

The question is: Will you meet it with chaos or with organisation?

Will you drown in possibilities or eliminate systematically and move courageously?

That's the practice. That's the path.

Until next week,

love,

aayush

hustle peacefully!